Mon 30 Jan 2012

No, You Go.

Posted by anaglyph under Movies

[22] Comments

As you have no doubt already intuited, this is going to be one of my very rare movie reviews. And I’ll say it now – it’s a long one. I make no apology, because in this case, I’m really going against both critical opinion and audience acceptance (and probably the Oscar for Best Film) so you can be sure I will say controversial and entertaining things.

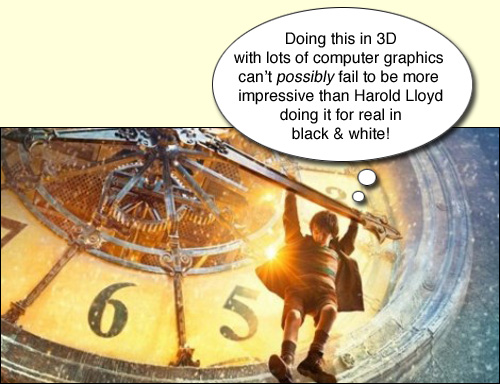

Yesterday I went to see Martin Scorsese’s fêted kid’s film Hugo. I made a special effort to see this film, and in 3D, because, you see I had been told two things about it (which turned out to be completely untrue): the first was that it’s ‘not really a kid’s film’, and the second that the 3D ‘is really great’.

Consequently, I will split this review into two parts, although there will inevitably be some overlapping. First, the 3D.

As many of you know, I have come to hate 3D in the movies. I didn’t always – I’ve long been a fan of the old anaglyph black & whites like ‘Creature from the Black Lagoon’ and ‘It Came from Outer Space’, and I have a fond spot for André de Toth’s seminal House of Wax and Hitchcock’s wonderful Dial M for Murder. These films, and others like them through the fifties and sixties, made admirable and necessary explorations into what seems like a logical direction for cinema to go. Unfortunately, there are many, many complications with making 3D work in the moving image domain, and those films never really conquered them. As a result, 3D was, decades ago, relegated onto a back shelf of cinema history, and despite several optimistic attempts to air it out through the 70s and 80s, it has never managed to get traction on the big screen. The difficulty in making 3D acceptable to an audience has always been blamed on the inadequacies of the technology – which is a fair criticism to a point – but as Hugo demonstrates very clearly, that’s only part of the problem.

Part of the problem it is though, and my experience with Hugo was no exception. This presentation was made using an active shutter system (XpanD, specifically) which basically entails a pair of 3D glasses that rapidly blank out alternating left/right images coming from the screen in such a way as to direct the appropriate image to the appropriate eye and so achieve stereoscopy. It is probably a superior system to the polarized X/Y axis technology (which I find supremely annoying) but only just. The first irritation became apparent as soon as the movie began – the damn glasses were greasy and dirty. So not only was I getting a dim murky image due to the attenuated luminance that 3D inflicts anyway, it was further degraded by great smears of refracted light in my peripheral vision. And try as I might, I couldn’t clean the glasses with anything I had to hand. So what – now everytime I go to the movies I have to remember to take a bottle of lens cleaner and a box of Kleenex with me? ((Later, as I left the cinema, I saw the staff frantically re-smearing all the XpanD glasses in preparation for the next show. I should have paid more attention to how they were doing this, but my eyes were still trying to adjust to seeing normally. My fleeting impression was that they were just wiping the damn things with a rag that was no doubt saturated with popcorn butter from all the glasses of the last five sessions. As with many aspects of modern cinema, the ‘advances’ in technology are mostly just creating more work for already underpaid people.)) This was almost distracting enough to make me want to leave thirty seconds into the film. When I pay $17 to see a movie, ((Violet Towne actually shouted me to this screening, so it was really her money. Sorry honey.)) I want to see the movie, not hazy tenebrous images filtered through the remnants of some kid’s hot-popcorn-butter-smudged fingerprints. Still, I had been told the 3D was ‘great’ in this film, so I persevered. I had, however, been distracted enough to miss the film’s set up. Good one 3D! Within a few minutes the major drawback of the active shutter system technology became apparent. The refresh rate of the LCD blanking technology is well below the frame rate of projected movie film, ((Unless the film is projected at a higher frame rate. Some systems are embracing a new standard speed of 48 or 60 frames per second to go some way to alleviating the refresh rate flicker problem. We shall see if that makes it any more bearable.)) and this creates an unpleasant strobing effect whenever there is a quick camera movement, or a bright, rapidly moving object in the frame. ((Moving 3D film images tend to have a problem with strobing on horizontal moving objects anyway, for very technical reasons to do with the way our brains detect rapidly moving hard edges.)) And guess what – this film has lots of falling snow. Little particles of bright 3D snow that zip and dart and STROBE across your field of vision. Horrifically distracting. And it hurts us, it hurts our eyeses, precious. Come ON, guys. Moving pictures have spent a century contriving to look fluid and seamless and now you expect us to put up with this kind of crap? To make matters worse, the opening sequences of Hugo are crammed with fast tracking sequences, fast action and rapid cutting. Scorsese flings the camera around like it’s a ball on a paddle bat. Technically speaking, for the moment 3D does not tolerate this kind of thing very well. ((And the corollary is that, for the moment, you should avoid doing it.)) It’s puzzling that Martin Scorsese, a filmmaker of extraordinary accomplishment, has not picked up on this fact.

And it’s here that I knew with absolute certainty that the 3D in this film was going to be anything but ‘great’. Oh, there’s a LOT of 3D, no question about it. Every shot is crammed with 3D-isms. There’s smoke and snow and dust and ashes and sparkles and cogs and dogs and shafts and fog and just about everything you could ask for to add visual depth to the image. It’s just a pity that it doesn’t add any other kind of depth. I can almost hear Marty screaming ‘There’s not enough 3D in that shot! More CG smoke – I don’t want them thinking I’m some kind of modern-day de Toth!’ ((André de Toth, the director of House of Wax was famously blind in one eye, so he could not actually see the 3D effect in the film. He evidently relied on the rest of his crew to make sure it was viable.)) The people who had been raving that the 3D of Hugo was ‘great’ just meant ‘there’s a lot of it’ – not unlike the people who tell me they think the sound in a movie was ‘great’ when what they actually mean is that it was ‘loud’.

Now, one of the the knock-on effects of having extravagant lashings of 3D in every shot is that your eyes want to look at stuff. In the real world this is what happens. Something moves in your field of view, you look at it. People talk, you look at them. A boat on a lake in the distance is pretty, you look at it. What never occurs in the real world, however, is that these things all take place within seconds of one another in a rapid replacement effect. There are two major catastrophic blunders that you can make with 3D, therefore, and Hugo makes them again and again and again and again.

The first is that you can’t just cut from one shot to another shot without any regard for where people’s eyes might be. In flat 2D filmmaking, we’ve spent decades honing our skills in such a way as to guide the eyes and ears of the audience in a carefully choreographed ballet of vision and sound. The art of montage – the ‘editing’ of the film – is an integral part of good filmmaking, and it’s one of the things that you study intensely as a young filmmaker. Thelma Schoonmaker, Scorsese’s editor, is an acknowledged doyen of the craft and it’s a mystery to me how the pair of them managed to hack their way through this film so badly. It’s almost as if Thelma said to Scorsese: ‘Marty, I don’t give a flying fuck about this 3D fad. I’m just cutting the film like I usually do.’ ((Like Tim Burton apparently did with Alice in Wonderland.)) The first ten minutes of the film had my eyes popping back and forward, left and right, in and out, up and down until I felt like Marty Feldman at a tennis match. No wonder people complain about 3D giving them headaches.

The puzzle here is that, again, it’s almost like the people who made this film have never bothered to watch, or learn from, the 3D films that have come before. ((I can’t believe, for instance, that Scorsese has taken nothing from Hitchcock’s masterful use of 3D in Dial M for Murder. Hitchcock only did this one film in 3D, and audiences of the time never saw it that way because – does this sound familiar? – they had tired of the 3D fad and the film was released flat to maximise its profitability. Nevertheless, he embraced the potential of the idea and absorbed it almost effortlessly into his filmic arsenal. As a result it was, and remains, one of the best uses of 3D to date, and I pine for one of the current batch of 3D advocates to come up with something half as well realised.)) 3D demands a particular kind of language just as 2D does, and you simply can’t barge into it with the same techniques that have served you in the past. For a start, it necessitates an understanding of what your eyes actually do when they look at things in the real world. The only time, for instance, that you need to snap your focus from a person talking in the middle distance to a big thing close to your face is when something extremely unexpected or confronting happens. In real life, this mostly causes you to jump backwards and knock your beer over. Now, when making a film, if it’s not your intention to smack the audience in the face like this, DON’T DO IT. And certainly don’t do it repeatedly, because the other problem here is that it makes your eyes do things they never, ever do in normal circumstances. Geez, for the first time in my life I feel like I could easily teach Martin Scorsese a thing or two about filmmaking. That should just NOT be happening.

The other appalling 3D fumble that is committed in this film, often in lock-step with the oafish cutting mentioned above, has to do with focus. This is a mistake that has been committed in every single one of the recent crop of 3D live action films ((But not with animated films. I wonder if you can work out why?)) and it makes me mad every time I see it. It’s the act of having things in the frame out of focus. Now, in 2D, we’re used to seeing this technique. It’s not a function of natural vision, but is a trick of photography, and it is used to direct the eye to something, or to throw it into relief. It works in 2D only because watching things on a 2D plane is not realistic, and so we have learned non-realistic tricks to help us make sense of the 2D image. The problem is it simply does not work in 3D. This is because – I hope you’re paying attention here Marty – we do not see things out of focus in real life! ((Unless of course we are myopic and don’t have our spectacles on. But I don’t need to tell you that no-one actually seeks out this state.))

Human vision is an amazing thing. It’s mostly amazing because only a small part of it is to do with optics. The rest has to do with a complicated system of visual processing in the brain. As far as the brain is concerned, things are only ever out of focus when there’s a problem. This is because our brain modifies our visual apparatus constantly, racking focus, pulling aperture, adjusting stereoscopic convergence, tilting and panning, and then gathering the information from this process to provide what appears to be one seamless binocular vision of our circumstances. Critically, it does this by ignoring a lot of stuff. One of the the biggest visual distractions it has learnt to ignore is anything that is out of focus. In your normal day-to-day life, you are very seldom aware of things that are out of focus.

Go on – try it now. Look around the room and try and see something in your field of view that is out of focus. You can’t do it! Whether it’s on your desk, over near the piano or out the window, your brain is constantly working overtime to make sure everything is properly focussed for you to look at. Things that it doesn’t focus on, it just doesn’t pay attention to. ((If you’re not following me here, you’ve misunderstood – as have most modern filmmakers attempting 3D – a fundamental mechanism of human vision. We do not see the world like a camera sees it. We have spent a century ‘learning’ how to see flat 2D images as portrayals of reality, but this is essentially not the way we see things in reality. Even if you have vision in only one eye, and are unable to resolve stereoscopy, you still don’t see the world like a camera does. It’s all to do with the fact that a camera is a purely optical system, and human vision is a computer-enhanced information gathering system.)) If people move in and out of your view, you can’t help but focus on them. If some fireworks go off outside, you focus on them. In fact, your world is in focus ALL THE TIME, if your brain can make it like that. And when it can’t (such as when someone thrusts a newspaper in your face and you have to step back to resolve it) you find it annoying and inconvenient. So filmmakers: WHY ARE YOU DOING IT IN 3D MOVIES? ((To try and illustrate the problem with a 2D analogy: imagine you are watching a film in a very wide anamorphic ratio – you know, Cinemascope or something. Now imagine that there are two characters talking. One thing you never do – unless you’re doing it specifically to call attention to something – is to put the two characters on the far left and right of the screen and cut between them as they talk. Why? Because the audience would be forced to snap their heads back and forth as the actors appeared first on the very left of the screen, and then on the right. It would quickly become very tiring and intrusive. We’ve evolved all kinds of film-making language to make sure that audiences aren’t popped out of the movie with irritations such as this.))

Let me give you an example of how horrible it is in Hugo ((This is just one example of many instances of it in this film – far more than I have seen in recent 3D offerings. James Cameron did it numerous times in Avatar, but only in the live action sequences. It never happens in the computer modelled scenes. I’ll leave you to reflect on why that is…)) In one scene, the eponymous Hugo and his friend Isabelle are standing in a clock tower looking out over Paris at the illuminated Eiffel Tower. The camera is behind them and tracks back. The focus is on the Eiffel Tower. The Eiffel tower is right in the centre of the frame. Hugo and Isabelle, in close foreground, are out of focus. This is irritating, but acceptable for a bit, since they are dimly lit and you are, after all, being directed to look at the bright Eiffel Tower. Then Mr Scorsese does something that is entirely acceptable – artistic and clever, even – in 2D filmmaking, but is brain-achingly stupid in 3D. He racks focus from the Eiffel Tower to our protagonists. In 2D, this would have the effect of drifting with our attention from the pretty-but-irrelevant centrepiece of the shot, back to the storyline. Movies do it all the time. So much so, that it is, indeed, a real skill to know at exactly which moment to force the focus pull in order to be in sync with the audience’s point of awareness. But CRITICALLY, this is a trick of 2D photography. In real stereoscopic human vision, we just don’t interpret the world like that, and so if someone does it in a 3D film, our brains are forced to do a very strange thing: we need to recompute the environment to try and make sense of it. In my brain, at that moment, it went something like this:

‘Oh, that’s a pretty shot of the Eiffel Tower. Weird out-of-focus people in the foreground, but whatever. Look at that beautiful model of Paris with all the lights on the Tower. I wonder if it really looked like that in the 1930s, electric light must… WHAT THE FUCK – EVERYTHING’S GONE OUT OF FOCUS. Oh. I see. I’m supposed to be looking at the actors now.’

To put it succinctly, if we were involved in this kind of scene in reality, we might look at the Tower, look at Paris, look at the kids, look back at the Tower – whatever. CRUCIALLY, nothing would ever be out of focus, especially the brightly lit BIG thing right in the middle of frame.

‘But wait just a goddamn minute!’ I hear you say. ‘It’s a movie, and movies are not reality. Movies do stylized tricky things all the time, and that’s OK! What about close-ups and Dutch tilts and zooms and stuff? They’re nothing like ‘reality’!’

Close-ups and Dutch tilts and zooms and jump cuts and a whole arsenal of cinematic hocus pocus has arisen, just like the focus rack, in the domain of the artificiality of 2D photographic image. They are techniques that ask us to make mental adjustments to the way we view a flat, already artificial, world. We simply cannot expect them to translate into a 3 dimensional space. They might, but if they don’t, we shouldn’t just go ahead and use them anyway, which is what’s happening here.

The mental disorientation with the focus shift that I’ve outlined above all happened very rapidly and quite subliminally it is true, but the significant point is that a contrivance of technique popped me straight out of the movie. As filmmakers, we spend every working moment trying to make sure that we don’t pop people out of the willing suspension of disbelief. To do so is the greatest single moviemaking crime you can commit. If we are to continue with this 3D thing we really need to find new ways to direct the attention of the audience, methods that don’t go against everything that evolution has wrought in us from the day that some mud-dwelling crustacean discovered that two eyes are better than one for avoiding being eaten. ((Lest you think I am talking out of my ass with all this stuff, consider that in my job as a professional sound designer, I have already been there. Sound people have been adjusting to spatial changes in film sound since we went from mono to stereo back in the 1940s. And now, with ‘surround sound’ we have in fact been dealing with a 3D environment for four decades. We’ve learnt a thing or two about what you can and cannot do. One thing I can tell you with absolute certainty is that many things that were totally acceptable in mono soundtracks just do not work in a full 3 dimensional spatial environment. We’ve had to learn new ways of making things work. And we’ve had to learn those new ways without making audiences hate the film because the sound hurt their ears.))

There are a dozen other types of similar terrible blunders of technique in Hugo: an extreme closeup of an eye looking through keyhole, where the keyhole is out of focus and the eye is sharp and crisp. (NO! Your eye would never see it like that! It feels WRONG because it IS wrong!); a horrible step-zoom where the focal plane changes every time a cut is made, forcing you to re-converge your eyes in a cascade of unpleasant jumps; ugly dissolves with convergence mis-alignments; ((Human eyes have a real problem with the kinds of artificial convergence thrust upon them in 3D photography. Again, this is a technical issue of human vision, and so is complicated to explain, but basically, when we look at objects we expect our eyes to refocus and re-converge stereoscopically at the same time. In the cinema, the focal plane is always constant (the screen) and the convergence is the only thing that changes. This is highly unnatural. We can do it, of course – otherwise photographic stereoscopy wouldn’t work – but it makes our eyes attempt to behave in a way that they would never naturally need to. It’s bad enough that movies force us to try to do it, but it’s MUCH worse when they make us do it rapidly and repeatedly. If you are the kind of person who feels nauseous when watching 3D, this is almost certainly why.)) rapid camera moves where you lose your point of convergence, scrabble around to find it, and give up because the shot just cut anyway; objects that are in focus in one shot and then out of focus in the subsequent shot, forcing your brain to try and make sense of why that is.

I won’t go on about it anymore – I think you get the drift. Everybody seems to be aware that 3D in the movies has to conquer many technical problems before it is a valuable (or even bearable) addition to the cinema experience, but as Scorsese’s Hugo demonstrates vividly, filmmakers themselves are probably its biggest liability. I simply don’t care to have the spectacle of stereoscopy if it hurts my brain, and I believe that this is what a great many audience members feel too, even if they can’t put their fingers on exactly why they don’t like it. I’ll raise it as a point of interest, even if I don’t know if it has any bearing on things, but I find it curious that the people who are pushing hardest for 3D, and making most of the 3D films, are largely old-guard filmmakers like Cameron and Scorsese and Spielberg and, soon, Ridley Scott. ((I admit to having a great deal of trepidation about Prometheus after sitting through Hugo. I was looking forward to seeing what both these directors did with 3D, since each was equally voluble about how much he loved it, and, in Scott’s case about how he would ‘never do another film in 2D again’. Now I just think I’m going to see the same old blunders committed over and over. I’m even inclined to see the movie first in 2D, just in case it’s actually a good movie and the 3D wrecks it for me.)) I’m not entirely sure why this should be – maybe because these guys are the only ones who can afford the technology and the budgets that warrant the extra cost of a 3D release – but what we need to see before 3D has even an ice-cube’s chance in hell of getting a foothold, is the arrival of some smart young filmmakers who can distance themselves from the ‘rules’ of conventional flat filmmaking and create a new language for stereoscopy that allows it to enhance the storytelling and emotion of a movie, rather than being the ‘next big special effect’. Until that day arrives, no amount of virtuosity in the mechanical/technical side of 3D is going to matter one whit, is my estimation.

Part 2 of this post will be coming up in a bit. If you think I hated the 3D, wait till you find out what I thought of the film itself…

22 Responses to “ No, You Go. ”

Trackbacks & Pingbacks:

-

[…] « No, You Go. | […]

Wow, a really long review with no spoilers. Impressive.

I remember the nuns showing us really interesting films in science class in the 70s. One in particular described fascinating research into how babies see, how adults see, how we physically read the page of a book and how our ‘seeing’ differs from our furry friends. Maybe Marty needs to see one of those films as well.

There’ll be spoilers in Part 2. It’s unavoidable, unfortunately.

Human vision is an amazing evolutionary accomplishment. Our ability to interpret the world through symbols is also an amazing accomplishment, but when these two things come into conflict, as with photography and stereoscopy, there will inevitably be pain if you try to use the rules of one to make statements with the other.

Just as early films were just versions of filmed plays, and so, were necessarily only interesting as a novelty version of plays themselves, so 3D films are, at this moment, only novelty versions of 2D. With the additional impediment that they hurt our eyes and brains.

I’m guessing it’s lots more work to render stuff out of focus in CG?

Is it really true that all these accomplished film makers are completely unaware of the part a viewers brain plays in interpreting film? As in – “What’s the difference? I’m pointing a camera at a 3D scene – 3D projection’s just gonna make my awesome shit awesomer!”?

It’s not more work to render stuff out of focus – in fact, it’s quite simple these days – but why bother if you don’t need to! Just use your world (which you control completely) to direct the audience’s attention where you want it. Don’t do it with focus, which is very artificial and so much unlike real life. The best of the recent animated 3D films – Monsters Vs Aliens and Despicable Me, for instance – effortlessly create stereoscopic environments that are relatively comfortable to watch. This is because animation is not bound by the rules and inconveniences of real-world photography.

And I know. This is what I think every time I see one of these 3D films – how is it that the directors and technical people don’t seem to understand the first thing about how we see? But I guess I’m more-or-less hardened to it, because I work with people all the time who haven’t the faintest clue about how we hear.

Sigh….

Umm – by the way – you left a certain desert town story out of that list of best animated films.

It actually wasn’t in 3D.

Did anyone care? I doubt it.

Disregard this. Not awake yet. Must have coffee.

Gawd and I thought I hated “The Descendants” . Here’s my review “A man’s wife is killed and he gets closer to his annoying daughters. Yawn.” I awoke to read “Clooney gives the performance of his life.” Life is cheap these days then.

Thank Ewok it was only in 2D.

And boy did they love Avatar, what a pile of shite…

I dunno, 3D isn’t any sort of drawcard for me, and just the look of Hugo put me off. Then again kids, urrghh.

It seems as if story vs effects is a lesson Hollywood hasn’t learned (or keeps forgetting over and over), and you’d think with HBO and Showtime kicking such goals they’d take notice of good storylines. Oh Well.

The King

I never had any intention of seeing it anyway

Crazy thing is that a lot of 3D tricks have been in use for centuries, in stage performances.

As you might remember, I’m a frothing, abject, unabashed lover of 3D in everything.

But… I haven’t been the the cinema much lately. I married someone who just doesn’t like cinema, and I have very little moneys anyway. So it’s quite possible that I might share your feelings on it, if I had.

What movies would you recommend as really well-shot in 3D? Those would be movies, I guess, with:

– Few “in your face” moments;

– few out-of-screen particle effects;

– instead of blur, guide the eye by having the brightest, shiniest, colorfulest, or movingest thing where they want the user’s eye to be;

– cuts that let the eye (if looking at the subject of the shot) remain at the same focus for the subject of the next shot;

– transitions between subjects in the same shot guided by objects; eg a bird flying from one thing to another; or weapon blows and ripostes.

– transitions between subjects in the same shot guided by the eyes of the cast.

I wonder how I would have handled a long focus shot like the Eiffel tower scene you described. Having a bird fly from the tower to the people would have been unrealistic and hammy and overly “omfg 3D coming out the screen, so using an object to guide their attention would have failed.

How’s about this, as my amateur effort:

Begin shot, emphasizing the Eiffel tower: night.

Tower is where subject of previous shot was, and is lit in flickering color by fireworks going off by it. Because this is 3D and in-screen fireworks look great.

Camera is up high, looking off a balcony with two foreground people at the railing, camera looking over their heads. They are in shadow, lit only by edge lights as they gaze away from the camera at the tower.

Fireworks fade; camera pans down so the people are framing the shot instead of at the bottom; the people turn to gaze into each other’s eyes; a light behind the camera ramps up slightly to illuminate their colorful/shiny clothing.

If panning down isn’t feasible, have them framing the scene, and have the camera pull back so that they move together towards the centre of the scene.

That kind of stuff.

Yes, your re-jigged version of the Eiffel tower shot would work much better. It doesn’t even need to be that complicated, in fact – just make humans do what they naturally do when they look at things. Instead of framing the shot for photographic beauty and then using a photographic effect (an effect that I reiterate is a learned effect; a piece of artificiality), simply have your actors occlude the Eiffel Tower by stepping into frame. Your eyes would quite naturally look at them. Or move the camera so that the Eiffel tower is no longer the centre of attention. Scorsese’s problem with this shot is that the whole sequence has been conceptualized around a 2D photographic technique.

If this was a ‘real’ situation, you could not stop a participant from looking at the Eiffel tower, but the natural human inclination is to pay attention to people speaking – 3D filmmakers will need to understand this kind of psychology. Rather than forcing the viewer to do something they would never do, they must learn to guide them.

If you want to see a good current 3D film, I recommend ‘Monsters Vs Aliens’. The 3D is beautifully realised, and the makers are very clever. I knew from the very beginning that this film was going to work, because in the first scene they (quite hilariously) reference a sequence from de Toth’s ‘House of Wax’ in which a street performer with a ball on a paddle bat turns toward the audience and makes the ball go out of the screen into people’s faces. This was a controversial sequence when ‘House of Wax’ was released, heavily criticized for ‘making people go cross-eyed.’ (It’s quite ugly, because it makes you try to converge your eyes MUCH too much). Well, the ‘Monsters Vs Aliens’ team take this idea as an homage, but the cleverest thing is that they make it work technically!

Animation lends itself to 3D much better than live action because you can control all the 3D ingredients completely. Distance between L/R eye, planes of convergence, camera movement, scenery – all can be brought to bear to make your sequence work. One thing you notice with MvA is that it is a lot less ‘cutty’ than a live action film, relying much more heavily on moving the camera for its dynamics. This is a GOOD thing with 3D, because every time you make a cut in a 3D film, you must work out how that’s going to cause someone’s eyes to behave. If you have fluid shots, all you need to do is make sure that the most important thing to be looking at is always drawing your attention. The thing is, James Cameron, at least, understands this. The animated sequences in Avatar (all the stuff on Pandora, pretty much) is SO MUCH better than the live action.

As far as recent good live action films in 3D, well, nothing I’ve seen fits that description. Some of them are really good examples of what not to do, Burton’s Alice in Wonderland being the pinnacle of crappy 3D (Burton refused to shoot the film in 3D, or even think about it in 3D, and so it was shot and edited as a 2D film and then ‘converted’ into 3D. And you can tell. It is full of the worst and most unpleasant blunders you could make.)

The film everyone who is interested in 3D should see is Hitchcock’s ‘Dial M for Murder’. I don’t know how easy it is to see in 3D these days, but I’m sure it must have been re-released. I’ve seen it twice in 3D, but a while ago. The impressive thing is that Hitchcock integrates 3D into his story. Instead of it being a special effect ‘add-on’, which it indisputably is in ‘Hugo’, it plays a focal part in adding to the drama and tension. I assume you know the plot, so I will give you some examples:

There is a scene involving the swap of a key which Ray Milland must steal from Grace Kelly’s bag. Hitchcock deftly uses the 3D to make the red bag the focus of every shot it’s in. You can see the scene here (it doesn’t even look like much in 2D – the 3D really ADDS something to this sequence).

In the famous scene where Grace Kelly is strangled by an assailant in her room, the 3D is masterful. Have a look here to refresh your memory. Imagine that in 3D! The lighting directs you always to be looking at the most important thing in the shot, as does the 3D. When Grace Kelly reaches back over the desk and finds the scissors, the power of the moment is EMPHASISED by the 3D. The shock of that moment is doubled when you see those scissors shining in the darkness right out over the audience. This is 3D doing something for the drama, not being used as a spurious special effect overlay.

‘Dial M for Murder’ is not a flashy 3D film. It’s a film where the 3D is being used judiciously as part of the filmmaking process, not slathered over everything like butter over popcorn.

I really wish I could direct you to a recent offering that had half the smarts of Dial M, but I can’t. For the moment, 3D is all about glitz and flash, things that have never managed to save it in the past. What we need to get audiences on side with 3D is a new Hitchcock – someone who understands what 3D can do, how it works, and how to integrate it into an already good idea.

I saw Tron in 3D in the IMAX theater. I noticed that IMAX versus regular theaters, that the IMAX makes one world of difference. I did happen to see Avatar in both, and in the IMAX, it really did seem to be a good use of the tech, but in the regular theater with it’s flat, small screen, the effects did not appear the same to me, and the movie seemed quite boring and of lesser quality by comparison.

Can you speak to the difference between something like an IMAX (do you have them down under) and a regular theater? I know that the sound system in the IMAX where my friend and I saw Tron was quite good (it seemed to be like a Bose system where normal theaters might be more like a set of earbuds or cheap Logitech speakers like I have in my house.).

Also, the IMAX 3D experience seemed much more natural in both instances than anything I have ever seen in 3D in any ‘normal’ theater. Of course, that could simply be the movies themselves, I suppose. I certainly recall the issues you mentioned much more vividly in Avatar in the regular Cinemark as compared to the IMAX, for example.

I’ve seen both IMAX and standard screen 3D. I’ve even seen 3D at the Arclight in LA, which is supposed to have some of the best 3D projection in the world. The quality varies so much from cinema to cinema and system to system that I think this in itself is a major liability to 3D. You really go to a 3D session not knowing WHAT you’re going to get. Personally, I’m not inclined to spend huge chunks of cash on that gamble.

I saw both Avatar and Alice in Wonderland in IMAX. The presentation of Avatar was pretty good, Alice was very bad (the IMAX system here uses two synched projectors. At the screening of Alice, one projector was out of sync by a small amount. I could tell this because on any cut to a bright frame, there was a kind of ‘swiping’ from left to right across my vision. Also, on rapidly moving objects, the 3D would completely de-cohere – a VERY unpleasant effect. I spoke with the head projectionist at length about this, and from at first being told ‘it couldn’t happen’, the story changed to ‘actually, I was on leave that week, so I can’t be sure’ to ‘OK, yes, you’re right – it was a fuck up and someone forgot to take their finger out, please have some free screenings on us’). Apparently I was the only one who noticed this, something I find completely remarkable, in that it was SO unpleasant to watch. I just don’t think audiences have much of a clue about 3D at all, and sit there dumbly accepting a really crummy piece of tech thinking that this is what they should be getting.

IMAX is certainly better than most standard cinemas for 3D, but still not great. Avatar was very good, but the 3D was not active shutter, and the polarized axis system leaves a lot to be desired (the polarization does not completely blank the image it’s not meant to be seeing for that eye – this happens because it’s impossible to make reflected light 100% polarized – there’s an inevitable amount of bounced light. This means there’s always a slight ‘ghosting’ in the image which I find distracting).

Sound in IMAX is mostly better than ‘normal’ cinemas, especially ‘Cinemax’-style cinemas which use pretty crummy speakers and cannot, because of the rigid screen, place them in the proper places. I say ‘mostly, though, because one of the things that really annoys me about IMAX is that they inevitably push the bass extension way too hard. This makes everything sound ‘chunky’ and that fools people into thinking the sound is GREAT. What GREAT usually means is that it’s boomy and not the way we mixed it.

Huh. Does the technology vary from IMAX to IMAX as well?

This whole article and the responses are quite fascinating, by the way. It is all rather above my head on the technical aspects at this point, but it mostly makes sense. I don’t think I have experienced much of what you are talking about with the out-of-synch though. We also saw, now that I think about it, the Green Lantern in an IMAX, and it seemed not quite as good as Avatar or Tron, but I think that was more the production quality to begin with than anything to do with 3D wizardry. Then again, I saw Thor in 3D also, but not in an IMAX, and it was quite decent in my opinion.

Oooh, but that Daft Punk in the IMAX was something else indeed, and to my ears was almost worth the ticket price itself.

“As filmmakers, we spend every working moment trying to make sure that we don’t pop people out of the willing suspension of disbelief.”

This is one of my fundamental problems with 3D movies. Besides the need to wear glasses over my glasses and the the dim, under lit picture due to the glasses, 3D (as currently both technologically and artistically done) feels fundamentally artificial to me, and it is extremely anti-immersive for me; it pulls me out of the movie from frame one. 3D in the 3D movies I have seen (none animated)does not look like 3D in real life. Perhaps most of it is more cinematic technique rather than technology limitations, but often 3D seems more like a shooting gallery with various fairly flat objects at different depths rather than true 3 dimensional objects that have depth of their own.

I’ve seen about half a dozen movies in modern 3D (all with polarized glasses) and Tron Legacy wasn’t too bad in 3D for me because the vast majority of the movie takes place in an artificial environment, and the artificiality of the 3D works mostly in the movie’s favor (much like the CGI of Jeff Bridges younger face works when inside the system but does not work well in the “real world” at the beginning), but I still hated the dim picture and having to wear glasses over my glasses.

The flat ‘layer’ problem seems to be different from person to person and from film to film. If 3D is properly photographed (and not the kind that’s added to 2D films afterward) I don’t see 3D like that – I do see rounded edges on objects and it does look natural, if often exaggerated. Films like Alice in Wonderland and Clash of the Titans certainly suffer from the layer problem – that’s because post-added 3D systems like Legend 3D uses must split the image into layers of depth to work. True stereoscopy shouldn’t have that problem, but for some people it apparently does.

It’s important to understand that stereoscopy is a trick, like stereo sound is a trick. Our eyes don’t actually see the way that 3D films make us see, for numerous reasons. For example, try this next time you go to a 3D film – tilt your head quite extremely to the side. The stereoscopy collapses completely. But do the same thing right now while looking at something. No problem – true stereo vision. This must necessarily happen with filmic stereoscopy, but it’s an extremely artificial situation for your brain; in the movies, you must sit with your head completely level for the 3D effect to be working maximally. You can tilt your head a bit and the illusion will persist, but I think it is probable that your brain is doing some computing to work out why there’s a problem, and that helps make you feel that what you’re seeing is ‘fake’. There are as I mentioned in the footnotes, also problems with focus and convergence being divorced from one another – very unnatural for your eyes & brain.

Circularly polarised glasses help somewhat, in that they let you tip your head further, but yeah: it’s still projected for left eye/right eye, so it still breaks in the end.

The “sharp edges” thing, though: even in “filmed as 3D”, I get that, too. I’m not sure why, but this one I think is a mental thing, because somehow it’s violating my expectations.

I have noticed a very similar “sharp edges” experience in real life, when I’ve had a new pair of glasses with a significant change in prescription – especially my first pair. Suddenly, you realize how sharp, real, and 3D the real world is! Everything has EDGES! Such amazingly crisp edges.

In real life, though, if you focus at part of an edge, the rest of the edge will almost invariably be out of focus in your peripheral vision. In 3D, unless they are deliberately blurring it the whole edge will be in focus, just separated.

Unrelated random pondering: why do we have two nostrils? Can some animals smell in 3D? I guess not, since smell is 0D. But smelling directionally, in 1D, maybe. Hammerheads, perhaps.

One thing it’s helpful to understand (as I spoke about briefly above) is that photograph stereoscopy is unnatural in another fundamental way in that it divorces convergence from focus. In the real world, when you look at an object, your eyes focus on it and converge on it at the same time. In 3D movies this is not what is happening. Your eyes are always focussed on the plane of the screen, but they vary their convergence according to where things are in the left/right (3D) field. This is really not like anything you’d do in real life vision.

In addition to that, we know that human vision is really a kind of ‘scanning-and-attention’ system and, in fact, we really only see a very small part of our visual field at any one instant to be ‘in focus’. The eyes are constantly doing little ‘scans’ of the environment (even when you think you are looking fixedly at something) and the brain is computing an illusion of the whole picture. Tests have shown that acuity in human peripheral vision is very poor – we pretty much only ‘see’ a tiny area right in the middle of our vision (I’m sure you’re familiar with the ‘blind spot’ illusion. The brain even ‘makes up’ visual information to preserve this illusion of continuity).

I think that the ‘layer’ effect has to do with this. In a 3D movie, we’re seeing a flat surface that is in focus from edge to edge for 40 feet or more. The scanning-and-attention mechanism has been completely scuppered because of the dissociation of focus from convergence, and so the brain is forced into trying to make sense of a highly unusual circumstance – it simply can’t process the image as it would a real environment. Well, that’s bound to throw up artifacts. I often hear people say that they ‘don’t get’ 3D, and I wonder if some people’s brains simply don’t know how to process the information of a 3D screen and just collapse it into 2D.

As far as stereo scent goes, it’s a good question. In humans the olfactory receptors are way up in the back of the nose, and I’m not sure they’re are even two discrete parts to them. My guess is that two nostrils are just an evolutionary side effect of bilateral symmetry. And it can’t hurt to have two, in case one gets blocked. I suppose that in animals with highly developed senses of smell, a molecule of scent arriving at one nostril before the other would give a hint at which direction it was coming from. I know some moths have highly developed smell directionality and can hone in on pheromones from miles away.

I think I saw something on TV once, some study, wherein they were testing the stereo smell of people by placing a distinctive smell (like chocolate or something) in a line on grass, and people were blindfolded and asked to follow it if they could. Ultimately they deduced through this that stereo smell works kinda like stereo hearing, in that people can figure out where smells are coming from simply by having the stereo smell, because they could follow the strongest part of that scent so accurately.

Of course, that was many years ago and probably not terribly scientific (I don’t recall if it was a segment or a whole show on some kids station or Discovery, sorry). It did stick in my mind for some reason, though, and now it appears to be relevant. Yay science and repressed memories…..

Please explain:

“…..but what we need to see before 3D has even an ice-cube’s chance in hell of getting a foothold, is the…..”

I always assumed the proverbial ice-cube had no chance at all in hell….so you mean ….before 3D has even no chance of getting a foothold?

Or am I just confused?

It was sarcasm infused with irony. I think it likely has no chance.