Mon 25 Jul 2011

Is It Just Me, or Is It Warm in Here?

Posted by anaglyph under Hmmm..., In The News, Mathematics, Numbers, Scary, Science, Skeptical Thinking

[30] Comments

One of the big topics in the skeptical community at the moment (like everywhere else I guess) is the climate change issue. It’s a subject that is as fraught with debate as that of Evolution vs Creationism, and indeed, has many of the hallmarks of that particular tussle. What makes it particularly volatile in this setting, though, is that many of the people who claim that there is no need to worry about global warming paint themselves as climate change skeptics, and take the position that they offer a rational approach to the debate. What they are in fact doing is voicing opinions that are in contradiction to MOST of the world’s knowledgeable climate scientists. Though they like to think of themselves as skeptics, this stubborn entrenchment in a belief system has earnt them, instead, the badge of climate change deniers.

I pretty much stay out of the climate change argument, just as I stay out of the Creationism debate. It’s not that I don’t have a strong view on global warming. I think the scientific evidence is conclusive that we have a looming disaster on our hands, and that it’s a disaster of our own making. Bothering to argue with the deniers though is the mental equivalent of jabbing a sharp pencil repeatedly into the back of your hand – a sensible person stops doing it pretty quickly.

The main problem is that, as with evolution, climate science deals with concepts that don’t come easily to the natural human way of thinking. With evolution it has to do with vast amounts of time (which we’re not good at comprehending) and the complexity of the vectors that come to bear on natural selection. With climate science, it’s all in the maths. I’m going to attempt in this post to show you why, even if you haven’t kept up with all the marginalia of the climate discussion, you should be afraid of what we’re doing to the planet.

At the outset I will state that my essay takes one idea as a given: that global warming is a human-instigated phenomenon. You should understand that a cornerstone of the denier’s ‘argument’ is that it isn’t, but I will stand behind the overwhelming scientific viewpoint on this matter. ((If the deniers are right on this and global warming is an inevitable natural process, then we’re in a handcart to hell anyway, and it doesn’t matter what we do. So we may as well make efforts to ameliorate the situation as not. An argument of financial imperative (‘it will ruin our economy’) is quite irrelevant because in a hundred years there won’t be an economy.))

OK. We’re going to talk about math in this, but you don’t need to understand numbers. And I promise you, it won’t be dull. This is a very scary story. I’m going to divide it into three chapters.

Chapter 1: Boiling the Frog

There is an old fable – it’s probably apocryphal but for our purposes it doesn’t matter – that says that if you take a frog and put it in a bowl of water over a burner and slowly raise the heat, the frog, unable to feel the very slow rise in temperature will make no effort to leave the water and happily sit there until it is boiled to death. In other words, it either doesn’t realise there is a problem, or, by the time it does, it’s too late.

The story illustrates a psychological phenomenon called ‘creeping normalcy’ (or in science, the ‘shifting baseline’ problem). Put simply, it says that if you have changing reference points, you can only judge what is ‘normal’ by what you’re familiar with at any given time. In this way, familiarity changes the baseline of ‘normal’ to whatever you get used to, and if things change slowly enough, ‘normal’ can wander an awfully long way from ‘acceptable’.

The first step towards understanding why the climate issue is so deadly is to understand that humans think like this as a default. Our brains don’t work well on timescales in excess of a few years. Our horizons are small. I’m not the first to mention the Boiling Frog concept in relation to the climate change situation, so its appearance here is no big revelation. But you need to keep it in mind as we head off to chapters 2 & 3:

Chapter 2: The Big Clock

I recently saw a comment on an article in The Conversation from one John Dodds, a ‘retired engineer’:

First a philosophical point: Climate Change is claimed to be complex. I claim it is NOT. It is simple physics – add more energy and the world warms up.

Mr Dodds’ opinion typifies the way in which most people believe that the planet’s climate system behaves – something like a Big Clock. A wheel here, a cog there, a spring yonder – all ticking away in a simple predictable manner that can be completely described if you do the right calculations. Most people think, therefore, that if we’ve caused some kind of problem with the climate, then all we need to do is to ‘oil the gears’ on the clock and everything will go back to the way it was. They believe that the problem is proportionate to the actions we take to correct it.

This is a massive and perilous failure of understanding. It’s a mechanical Newtonian notion of the way things work that is fine for pipes and balls and clocks, but breaks down catastrophically when applied to something like climate behaviour. To grasp why, we have to venture into the frightening, mind-bending and completely unintuitive world of complex systems.

First, let’s consider the pendulum in our Big Clock. As physical systems go, this is about as unadorned as you can get. A swinging pendulum exhibits what is known as simple harmonic motion ((For small angles of swing. As the angular acceleration increases things become a little more complicated, but for our purposes we can assume true simple harmonic motion.)) and it is a very reliable behaviour that allows us to build a clock that will behave predictably and dependably. A simple pendulum is mathematically very straightforward. Its properties can be described completely in terms of the length of the ‘rod’ of the pendulum, gravity, the mass of the ‘bob’ on the end of the pendulum and the angle of swing. If you know these things, you can predict exactly how this pendulum will behave. This uncomplicated mechanism works great for a clock, and it’s fairly tolerant of perturbations in the system: if you push the pendulum a little hard, it will dampen down to its normal swing pretty quickly. You need to be pretty violent to cause the clock to have problems big enough to effect its function.

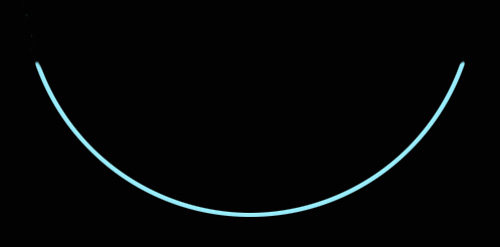

This is the kind of path we could expect the bob on the simple pendulum in our clock to trace. Every time:

Unfortunately for us, the climate system isn’t driven by a simple pendulum.

Let’s consider a physical system only a tiny step away from our Big Clock’s single pendulum: the double pendulum. A double pendulum makes one small alteration to the simple pendulum model – instead of a simple bob at the end of the pendulum, you add another pendulum. This very unassuming variation has sudden and profound effects.

Here’s a computer simulation of the path traced by the tip of a double pendulum:

If that looks weird and science fictiony to you, let me assure you that double pendulums behave exactly like that in reality. There are dozens of YouTube videos that show them in action.

You can see how this one small change to our pendulum quickly throws a simple harmonic oscillation into a volatile and complex motion. The double pendulum system can be very easily described, ((We still know the lengths of the rods, the mass of the bobs and the gravity coefficient.)) but its ultimate behaviour cannot. Each time you set it swinging its bob will trace a completely different path in space because, crucially, a double pendulum is very sensitive to initial conditions. Unlike our clock’s pendulum, we can’t accidentally give it a bit too much of a shove and have it simply settle back into its predictable ol’ groove.

Imagine, now, that you have a pendulum with n arms, each with a bob with a mass that is a variable coefficient ofn, n points of articulation on each arm, and variable gravity. It doesn’t take much of a leap of imagination to understand how wildly such a device will behave. In fact (and this is where most people fall off the bike), for surprisingly small values of n, no amount of computing power in the universe can ever predict the path of motion it will describe!

Well, the Earth’s climate is exactly such a system.

Unfortunately one thing that tends to be a little confusing with this is that climate scientists often speak of ‘climate modelling’ and to many people this sounds again like they’re talking about some kind of Big Clock: you stick in all the variables into your computer and ‘ping’ – out comes the behaviour that the Big Clock will exhibit. If it were only that easy.

When you look up a weather report on your i-Device of choice, you’re seeing climate modelling at work. One thing I probably don’t have to tell you, is that you shouldn’t rely on the information more than a few days ahead. That’s the state of the art in climate modelling. We’re just not very good at predicting the behaviour of complex systems (like weather) even a few days in advance. Here’s the kicker: it’s not our fault! These systems are inherently unpredictable. Even if we had super-super-super computers, we couldn’t do it. Even if we had a computer that could take ALL the variables – and that’s a HUGE amount of variables – and then run the simulation in real time to see what it did, it would do us no good – we would get a different outcome every time we ran the program. Just like its very simple distant relative, the double pendulum, a complete detailed model of a complex system like the climate is critically dependent on initial conditions. (We actually do have such a computer – it’s called ‘Reality’. The only accurate simulation of what the climate will do is the climate itself).

So, when you hear scientists talk about modelling the climate, you should not understand that to mean they are trying different kinds of wood for the clock case, or a new type of oil to make the gears run smoother. They mean they are making their best educated guess at the Big Picture of what might happen if they picked enough of the right factors to plug into their equations. Just like you understand the weather man to be doing when he tells you that in a week’s time it looks like rain (are you starting to get nervous yet? No? Then you’re not following me).

So what’s the problem, right? We don’t know what the weather will do – why is that different from any other period in our history? Why are we suddenly worrying now? Well, one of the things that modelling can predict pretty confidently is trends. Just as we can say that a double pendulum pushed gently is unlikely to do the crazy loop-the-loops that we see in the same system dropped from a higher angle, models can tell us that when we change something in the climate system too much, we’re likely to see unpredictable behaviour. In recent times (the last few million years or so) the climate has been ticking along like a gently-pushed double pendulum; little flurries here, little irregularities there, but for the most part, predictable enough for life-forms to have evolved strategies to cope. Things do change, but they change slowly. The system keeps itself in check through millions of years of self-modification that has allowed it to reach a relatively stable, though delicately balanced, equilibrium. The evidence is clear, though, that over the last few hundred years (a VERY short period by geological standards) humans are swinging the pendulum’s arc wider and wider by the simple act of burning things. We’re taking carbon that has been for eons locked up in the biosphere and chucking it into the atmosphere where it has started to imprison the Earth’s heat. We can, therefore, state with a high degree of confidence (based on an enormous amount of accumulated data) that the planet is heating up monumentally faster than it ever has before, and that that heating-up is concomitant with the technological period of humans. ((We’re excluding events that happened in geological times of many hundreds of millions of years ago, where lots of weird climate events happened. They are not relevant to our argument because we weren’t involved. If we had been, we’d be dead, which is of course the issue at hand.))

But when climate modelling scientists make a ‘prediction’ that the temperatures will rise 3 or 4 degrees by the end of the century, you should not think of that as a jolly nice warming of the winter months, and the odd extra scorcher in July (or January, depending in which hemisphere you live). You should instead interpret it to mean ‘We figure the whole system is going to heat up, but how it delivers that heat, and to whom, depends on the swing of the double pendulum…’ What you should expect is periods when the weather seems just as it always has, interspersed with occasional outbursts of extreme behaviour. For a while this will seem normal, and you will be as happy as a frog in a warm pond. But this extreme behaviour itself will start to interfere with the system – it’s another phenomenon of mathematics which those in the know approach with respect: feedback. And that feedback will almost certainly affect the system in ways which we can’t even imagine. ((We don’t really have much of an idea of the way the climate system is held in such delicate check anyway – global atmospheric behaviour is without doubt one of the most complex systems we know. All we can say for certain is that that if it changes much, we are in trouble.))

This coupling of complex behaviour and feedback is the thing which frightens the scientists, because it’s something with which the world of science has become very familiar in the last fifty or sixty years. We know that a complex system exhibiting instability and feedback can suddenly and capriciously become chaotic. That is, the system is likely to reach a point where even modelling is completely useless – it just goes completely berserk.

Trust me when I say that we really don’t want to see our climate system go chaotic. If we hit that point, it is likely that the great majority of the human race will suffer. ((It should be understood here – because I often think that it’s not – that the planet is indifferent to this problem. You hear climate deniers putting forward ideas like ‘Well there have always been periods of global warming’ or that ‘Sea levels have changed many times though the Earth’s history’. Well, sure. But mostly, there were no, or few, humans around, and other creatures were affected by these events, often in the form of species-wide extinctions. The Earth was once a giant greenhouse, covered with plants. But WE could never have lived in it. The planet would probably survive quite extreme results of our global warming efforts – it’s just that we wouldn’t.))

Chapter 3: Jenga

The kind of critical instability that I’ve just described is a lot like the game of Jenga. The Jenga tower will remain upright as long as the system is stable around its centre of gravity. If you lived on top of the Jenga tower, you would probably be aware of nothing at all as pieces are removed. Maybe the tower might wobble a bit, but, hey, things look pretty normal. Every removal of a Jenga tile is exactly the same kind of small effort, but each one of these small efforts moves the system closer and closer to critical instability. When the Jenga system reaches this point, the collapse into chaos happens rapidly and catastrophically, with little warning.

Well, that’s where we are right now. The tower is wobbling a bit, but everyone is saying ‘Hey, the tower has wobbled before and we were OK – what’s the problem? Worse, we continue to slide out the pieces, because that’s what we’ve been doing for years and it’s been just fine.

Unfortunately, this kind of situation is the very worst sort of thing to try to get resolved by a ‘popular vote’. When you combine the Boiling Frog situation with the Big Clock scenario and stir in a whole lot of poorly educated ((I say ‘poorly educated’ because I think that even the great majority of people who are literate do not have a good grasp on science, nor on rational ways of thinking. Any of you who have been reading TCA for a significant period of time will understand exactly what I mean here.)) points of view, you just get lots of personal assessments of the problem – or debates about even whether or not there IS a problem – and a bucketload of total inaction. The grim truth is that it’s a state of affairs that seriously needs everyone on the planet to be in complete agreement, or we will, without doubt, plod our way into extinction.

The way it stands at the moment is that the vast majority of people are either uninterested or confused, a small minority is in denial and beset by superstition and petty agendas, and another small minority is informed but frightened, frustrated and powerless. I think that what we are seeing here are the ramifications of a massive failure as a species to improve ourselves by putting emphasis on the capacity to understand our world through observing it properly. That is, through science. It is of no use to put an appropriate course of action to a popular vote in this instance, because the holders of a popular vote aren’t equipped to understand what it is they’re voting on. And frankly, I think we’ve run out of time to get them up to speed. Added to that is the negative influence that whatever we need to do will, most likely, cause great inconvenience to a large number of people, and will include increased poverty, loss of jobs, deprivation of luxuries (and maybe even necessities for many) and a general willingness to just suck it up and take a beating. It doesn’t take much insight to see that we’re never going to get people to volunteer for that, unless they become very afraid indeed (by which time – I emphasize once more – it will be way too late).

If ever there was a time for the leaders of our nations to listen to the science, and act decisively and quickly for the good of human race, this is it.

___________________________________________________________________________

Image of the Earth courtesy NASA and the Visible Earth project.

Sadly, I don’t think your blog readership will pass on this post to the right people. Or even to enough of the other people.

But we are right to be afraid.

Oh, I’m sure you’re right. I think we are at a bad place with this – I’m not sure enough people will understand the complexity of the issue soon enough to do anything about it. I feel completely helpless about getting the ideas across to friends and family, so I’ve tried to illustrate it as clearly and simply as I know how.

I put it here as another place that people might stumble on if they’re trying to find out more about the subject. Perhaps it will help one or two people to see a little deeper into the problem.

It is interesting that you essentially close off debate or questioning of your claims at the start, so it is not too surprising that you do not want the rest of us to have any say in the matter. You and the minority of the informed know how to save the world, so we should put aside democracy and representative government. And really, what could go wrong with a small self chosen elite dictating to the majority?

I close off the debate only because I think, like many other informed people, that there is no debate.

The democratic argument is nonsense and shows you haven’t thought through the consequences. You would go with any decision of an ignorant democracy? Really?

You also imply that I haven’t the smarts to know the perils of autocracy. I do. But sometimes stupid people should not be driving the bus.

Instead of writing all this text, couldn’t you have just used some simple graphics, man?

Part of the problem is that we’ve created a population that can only think (and read) in soundbites. The simplest illustration of the problem I can think of is the roulette picture at the top of the post.

Soundbites and Powerpoint presentations may kill us all someday.

“Powerpoint makes us stupid” -A US General:

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/27/world/27powerpoint.html?no_interstitial

Powerpoint and the Columbia disaster:

http://www.edwardtufte.com/bboard/q-and-a-fetch-msg?msg_id=0001yB&topic_id=1

Yup. We have gotten to places where our need for natural comprehension is being challenged by situations that are just too complex to navigate by ‘common sense’.

And, as with the Columbia disaster, we tend to seek expediency over proper assessment of risk in these complex cases, because our ‘natural’ understanding is inadequate to process the problem in the way that we might deal with a tiger in the forest, say.

I wonder if anyone’s made a time chart showing ‘exceptional’ weather patterns (floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, drought, heatwaves, coldsnaps, etc)over the time of recorded weather. We may note a clustering of such the last few decades.

Seems to me that the only question can be how much climate change is due to human activity and natural cycles. Then again this moot point doesn’t really matter if the climate system crashes.

“Sigh, pass the bong and Johnny Walker please.”

The main difficulty with what you’re suggesting (and people are actually doing it) is in deciding what, exactly, constitutes ‘exceptional’ weather. It’s the shifting baseline problem again. We only have accurate weather records for something over a few hundred years. It’s too small a slice to be able to see any trends. In any case, if it’s typical of a system heading towards criticality, by the time you see those kinds of visible signs, there is nothing at all you could do to stop it – it’s already heading into chaos. That, in case you didn’t get my subtext, is the scary part. By the time there are indications that are plainly visible to ‘the man in the street’, we may as well kiss our asses goodbye. The fact that some of us will be able to say ‘I told you so’ is cold comfort of the most depressing kind.

As far as the human vs ‘natural’ argument is concerned there is little doubt among researchers that warming and human CO2 production are linked. As our population has risen, the carbon dioxide volume in the atmosphere has also risen, as has the global temperature. It could be a coincidence, but no-one with proper climate science training believes that.

The deniers, of course, try all kinds of desperate tricks to divorce those three vectors from one another, arguing variously that the atmosphere isn’t heating, or that the rise in CO2 isn’t a problem (‘cos that will cause more trees to grow and fix everything – or some daft thing), or that the figures don’t correspond accurately enough with human industrial activity (‘cos they don’t know how to read graphs). In general, they argue like Creationists, nipping and picking at what they perceive as tiny inconsistencies in the arguments, but completely unable to understand the structure of the science.

If you’ve ever engaged in a ‘discussion’ with anyone who supports an irrational belief, this landscape is very familiar. You find yourself exhaustingly following bankrupt references or links to science that doesn’t support their argument (but they somehow think it does), or fringe data that isn’t robust enough to draw conclusions, or ancient literature that has long since been discounted, or opinions by famous people with no actual credentials in the pertinent field, or anecdotal evidence, or circular reasoning or just plain fruit-loopery.

As I said above, climate science, like evolution science, isn’t easily graspable via folk wisdom. In fact, evolution is EASY compared to climate science, and that’s a debate that’s raged for centuries.

Hi Rev, don’t really want to be a pedant, but the “2” in CO2 should be sub-scripted, not super-scripted. Nice post though!

Whoopsy! Don’t apologize for being a pedant – we love pedants here! (Except for Atlas – he’s just a smartass.)

I should have spotted it – it’s to do with the way you signify sub and superscripts in HTML – [sub] and [sup] My brain was on automatic coding.

“In fact (and this is where most people fall off the bike), for surprisingly small values of n, no amount of computing power in the universe can ever predict the path of motion it will describe!”

As a side note, even 3 object, dynamic n-body problems are very difficult to calculate. This is the main reason why it’s impossible to extrapolate the orbits of the planets in our solar system more than a few dozen million years in either direction, past or future.

Considering how congress is currently playing a game of chicken with the debt ceiling over whether or not to include “revenue increases” as part of the solution, I think we may be screwed in regards to AGW. Nobody wants to be responsible for the necessary and unavoidable pain of the solution.

In any game of chicken, the stupidest person prevails. (Unless there’s a head-on collision, and then both sides lose.)

If our governments don’t get it, we totally are screwed. It’s bad enough if their hands are stayed by ignorant democracies, but it’s worse if they consider that AGW is an issue less important than all the other things on their plates and just ignore it.

In my country, where the population does have a concern about AGW (albeit a kind of lazy ‘I don’t think this is good’ kinda way) there is definitely pressure on the political powers to do something. The problem is that, given this instruction by the voters, they don’t actually then go and consult the people who know – the scientists. And if, as the current Australian government has done, they should act in such a way that the voters perceive a hardship, then all hell breaks loose.

The People want the problem fixed, but they don’t want to stop driving their SUVs or give up their Home Cinema system. THAT is the the real problem with putting this to a vote.

Children don’t want to forego their candy, even if it is rotting their teeth.

I find the whole issue about “skeptics” to be particularly interesting on this issue. It’s kind of like those who immediately distrust western medicine and say that it’s because they’re “skeptical”. As a science-based person, I have found that those who understand science the least tend to be the most vocal about being “skeptical” as though scientists have a reason to lie. Being skeptical about a person’s motivation in one area – especially as an outlier – makes sense. Believing that thousands of professional scientists who have spent their lives studying these things are all lying and to no end just reeks of insanity.

So my question to those who say that it’s all a big lie – why would the vast majority of the scientific community lie about this? What could they possibly gain?

Ah, don’t you see MoonJewel – it’s a conspiracy! The Evil Scientists want to take control of the planet so that they can create their hideous FrankenMonsters and experiment on our children. Or something.

The popular argument among my relatives appears to evoke the old spectre of Communism. Giving up stuff for the common good is just a little too ‘pinko lefty socialist’. I frequently hear the complaint that the strategies offered by our government will ‘put people out of their jobs’, or ‘hit the pockets of those who can’t afford it’, as if the problem is going to be solved WITHOUT these kinds of things happening. They act like fat children terrified that they might be served up brussels sprouts instead of a cheeseburger, never mind that the cheeseburgers are killing them.

The ‘skeptics’ in the climate change issue argue in the same way that woo-mongers do: ‘Your mind is closed! If you had an open mind you’d see I was right!’ What they fail to understand is that keeping an open mind is about facing truths that are unpleasant, no matter how much you don’t want to hear them. What they are actually advocating is the worst kind of close-mindedness: ‘I don’t want to hear what you’re saying! You’re making it up so you can take advantage of me in some way that I can’t fully articulate but must be true’ (because the alternative is very hard to contemplate).

All good stuff Rev, I think we may reach a criticality in our financial system fairly soon which ironically could be a good thing for the planet in the long run. As for the climate, well…

On the issue of pedantry I feel like a pedant but I have to point out that the double pendulum equation has in fact been solved by Michael Schmidt (well really his computer actually) as reported in New Scientist in the March issue earlier in the year – just FYI.

Sadly I don’t think our leaders listen to science all that much, they’re aware there’s a problem sure, but when you factor in short terms in office, the demands of big business and the economy, then the ‘voters’ – well you can see the problem right there. Global warming shouldn’t be an impediment politically, it should be top of the list and I think there is enormous grassroots support for almost any initiative in this regard – in fact this alone pretty much ushered out the Howard government in this country.

Since then though we have seen little progress and now the Carbon Tax is mired in the politics of popularity rather than seen as an ethical imperative. Why do we still have coal power as our primary source of electricity and why has BP Solar bailed to India – we’re just not getting it right here at all.

Like a lot of things in life it all just seems too hard for mankind as a species and I suspect it will just keep on getting harder and harder. I don’t think any of us will be looking to have a ‘comfortable’ retirement – far from it.

All I can do is keep turning off lights and using the car as little as possible till I come up with a useful and practical plan for rewiring the house, until then I’m just an armchair greenie. We’re all to blame in our own way. I would give up my saturdays to build windmills and plant trees, I wonder why social initiatives like this aren’t heavily promoted and sponsored… Hmmm let me guess.

The King

Interesting, I wasn’t aware of that. It serves to emphasise my point though; it has taken us till now to get a solution, and that solution wasn’t achieved by humans, but rather by a computer pattern-matching system. The focal point is that this is only a double pendulum. If it’s taken that long to figure out how a double pendulum behaves, it’s not hard to see that we’re a long way from understanding a triple pendulum. And an n parameter pendulum? Like I said, comes a point when the best model of the system becomes the system itself.

The fact is that if everyone in the West was an ‘armchair greenie’ (as I am too) the problem would not be nearly so bad. It is not our use of energy that is the problem. It is our extravagant use of energy. We can slow things down remarkably by relatively small measures – that’s what’s so frustrating about all this. If we reduced energy consumption by just 20% (an easily achievable target) the effects would be significant. But a lot of people can’t bring it on themselves to walk to work a couple of days a week, or not turn the air conditioner on until they really need to, or eschew a gas-sucking 4WD for a small 4 cylinder car under the completely bogus aegis that the 4WD is ‘safer’ (an image that has been irresponsibly promoted by automobile manufacturers).

Planting some trees sure would help, as would some active promotion of cycling, walking, public transport and consuming of local produce. But the few people who are doing things like this are TOO few. It has to be a world-wide effort or it is futile. And for us to try and take up the slack of all these people just won’t work – we can never make up for the profligate consumption of those who don’t care, or don’t understand. That’s why I hold little hope of it happening in any other way than through compulsion. It’s not what I desire to be the solution, but like I said, I think it’s way too late to educate people enough to get them to take those responsibilities on themselves.

but isnt part of the problem that the world seems to be doing nothing. We need another world gathering where a global position can be taken.

hopefully glllard’s plan with see squillions of money pour into alternative enegry, and the results from all this R%D will see improvement that we can flog off to the rest of the world.

another issue is that the people dont trust the pollies, either ‘the mad monk’, or the ‘its the new me’ gillard. Whatever they say, people are not listening, possibly since they dont trust them.

if the two major parties cant sit down and work out some decent ideas thats best for the future, i can understand people saying ‘why should I bother’. And after the mining companies got the government to fold ont the super profit tax, I doubt the public trust companies to look beyond profits.

and this is from someone who added solar hot water at home, insulation in the house, and uses public transport to get to work.

on the good news, at least you dont hear too much news about how we need to reduce the numbers of people that are on the world, ie lets sterilize the third world.

Unfortunately, any palatable solution you can think of calls for a large number of the world’s population to suddenly get smart. I really don’t think that’s going to happen. I think if the initiative doesn’t come from politicians paying attention to scientists, we’re basically fucked.

And we probably do need to curb the population. It stands to reason that, in an ever-expanding system of breeding, you’re going to run out of resources eventually. Sooner or later there will be too many people to support. When will that time come? Who knows, but we are certainly close to it. I’m not suggesting large scale sterilization, but it’s a problem that does need to be addressed somehow. Again, these are not BIG changes that we’d need to make. If we could keep the world’s population stable at around six to eight billion, we’d probably be fine. But if we start seeing figures of ten or twelve billlion people on the planet, again, I think we’re fucked.

From where I stand, I think things look bleak. I seriously, really, truly, desperately hope I’m wrong.

It truly is frightening. Society applauds couples for breeding. The more kids, the louder the cheers. I get into trouble when I don’t cheer along.

My wife and I started to look into adoption, but with the red tape and $20,000 start up fee, who would want to?

It’s a tricky problem. By criticising population expansion you are sticking your finger in a pie made up of ‘my basic human right’, ‘that’s what nature intends’ and ‘that’s how we keep capitalism intact’. So you offend 95% of all people instantly.

Yet commonsense dictates that a rising population and finite resources must come into conflict at some point. All the people in that 95% think that ‘some point’ is something they need not worry about. But somewhere, sometime, someone is going to need to worry about it. It’s just maths.

http://www.grist.org/list/2011-07-21-nyc-mayor-bloomberg-gives-50-million-to-fight-coal-michael-bloom

Speaking of lobster pots (via boingboing).

Average temps have risen half a degree (wussy little American degrees, but still) from 1971-2000 to 1981-2010.

Beware of thinking about how this tells us that the decade 2000-2010 was 1.5 degrees warmer than 1071-1980 – the longer the timescale we look at, the more likely we are to be looking at climate instead of weather.

I don’t think that climate denial can so easily be brushed away with “a sensible person stops doing it pretty quickly”. They generally pose serious, logical questions that need a response.

To me, both sides sound like each other: accusations of cherry-picking abound on both sides, and for every graph one side whips out, the other has a response that says the opposite.

The main problem of the duelling-graph syndrome is that we’re not yet out of the “background noise” point. The 30-year average is a good climate measure, but by the time the evidence becomes completely incontrovertible with other graphs, we’ll be completely screwed.

Climate change proponents whine feebly that they can’t be bothered to tackle every single cherry picked graph. But that’s what *needs to be done*. The denialists don’t have this problem: they are happy to tear apart any piece of evidence the proponents come up with, and to me, that is GOOD SCIENCE.

Failing to address, loudly and publicly, the specific issues raised by the denialists is not just lazy, it’s potentially deadly, and is why climate denial has gained such a foothold in the US.

Well, and also because the scale is likely to be non-linear. It is certain that the amount of CO2 being freed into the atmosphere is non-linear, and this correlates with a non-linear rise in population increase and corresponding rise in industrial activity.

Most of the material I’ve seen shows a trend towards temperature rise. Sure, we should be cautious about specific forecasts, but it is highly likely, in the view of the great majority of scientists with expertise in climate science, that this trend is real.

Most ‘serious, logical questions’ that have been posed have generally been comprehensively and effectively addressed. There are a very few arguments from the deniers that hold weight among the scientific climate community, and those ones that do are generally esoteric challenges that are difficult to assess with the available data. There is a comprehensive list of the main deniers’ arguments and the rebuttals here, if anyone is curious.

Except for the fact that the people whipping out graphs to illustrate the hypothesis in favour of AGW are overwhelmingly people who have spent their entire careers monitoring the climate, and the ‘skeptics’ comprise a very small number of climate scientists among a group consisting of scientists outside their field of expertise, opinionated laymen and loonies. There are very few loonies on the ‘it’s happening’ side.

In my experience (and this is a personal conjecture – sue me), the loons tend to accumulate on the side of no substance, no matter what the issue: Creationism; Y2K panic; moon landings; Morgellons’ disease; Anti-vax; ShooTag; homeopathy; alien abductions; crop circles. You name it.

In other words, that’s the side the science isn’t on. Along with that you get the conspiracy theories to explain why the scientists are doing it; they want to feather their nests; they’re in the pay of the government (for some reason); they’re evil and/or mad; they want to control us.

Like I said – I would really like to be proved wrong on this one, but it’s showing all the hallmarks…

Agreed. But the climate scientists aren’t just going on the graphs. We’re seeing all kinds of physical evidence of accelerated warming, and the hypothesis of increased CO2 being a liability is a good one. We’re running a scenario of reasonable plausibility with this, and it seems to me that the best strategy, when offered reasonable plausibility, is to adopt caution. Especially when you’re dealing with a complex system.

I strongly disagree. This is exactly the kind of ploy that the Creationists use, or the moon landing denialists, or the anti-vax movement or even the ShooTaggers (you yourself have seen first hand evidence of how this kind of mindset works – make a claim/change the claim. Make a claim/change the claim. Repeat ad nauseum). And, as anyone who has engaged those people knows, you end up spending shitloads of time looking at ‘data’ that is spurious for one reason or another. C’mon – it’s plain common sense: if someone was to present some data that threw a strong negative light on AGW why wouldn’t anyone take notice? You have to invoke a conspiracy to explain it.

But people ARE addressing it loudly and publicly. The problem is that the denialists, like the anti-vaxers, have on their side the fact that the general population does not have enough science to be able to differentiate a good argument from a pseudoscientific argument. Plus, as always, a facile simplistic explanation based on ‘folk wisdom’, delivered with a loud voice, will always get cachet against a complex argument that needs some background to be understood. Factor in the general population’s reluctance to give up a way of life that they like, and you have a mighty big hill to climb. It’s just easier to form a view that things are fine.

THANK YOU, Reverend, for that link you included!

Loved the article. I’m doing climate change extension in my day job and I do like your point about complexity.

How can we even start to educate the masses about a subject that scientists have had ten years of training and done countless years of research on to understand? So we end up with simplified versions of the analysis and argument and then the deniers can pick holes in these. “Hey look, it’s just a model and they can’t even get the weather right.”

I like this video:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3wHKBavY_h8

Hahaha! Yes, that video just about sums it up doesn’t it.

Sadly we’ve come to a sort of ghastly deadlock with this problem – complex systems are not something you can expect to grasp without a bit of study. And, unfortunately, the people who are doing the study and know what they’re talking about are treated with suspicion.

Couple that with a need to make decisions that are uncomfortable and probably costly and we’ve made ourselves a nice comfy handcart, which is heading rapidly to the hot place.