Fri 30 Oct 2015

Underexposure

Posted by anaglyph under Blogging, Hmmm..., In The News, Web Politics, Words

[6] Comments

If you have any finger at all dipped in the vast ocean of blather that is social media, you can’t fail to have noticed yesterday’s flurry of hand-waving over some comments made by internet luminaries Will Wheaton and Matt (The Oatmeal) Inman. For those who aren’t mainlining Facebook and Twitter, and didn’t catch it, the whole thing revolved around the Huffington Post doing what it does – sucking content from anywhere it likes without paying for it, and then regurgitating it to the world – and Wheaton and Inman getting on the wrong end of that deal (the ‘without getting paid’ end).

In Wheaton’s case, the Huffington Post wanted to use a previous post from his blog, but declined to offer any compensation when he asked for them to actually fork out for it. Wheaton wrote about it, quite reasonably, in a piece entitled “You Can’t Pay Your Rent With “the unique platform and reach our site provides— riffing on his earlier Twitter comments “Writers and bloggers: if you write something that an editor thinks is worth being published, you are worth being paid for it. Period.” and “This advice applies to designers, photographers, programmers, ANYONE who makes something. You. Deserve. Compensation. For. Your. Work.”

As for Inman, the HuffPo hotlinked one of his Oatmeal strips, and he then quickly link-spoofed them with an image that said “Dear Huffington Post. Please don’t hotlink images without permission. It costs me money to host these. Here’s my monthly bill”, with said bill attached. This morning, he followed it up with an amusing cartoon commentary.

At least they asked Wheaton whether they could use his stuff. They just pinched Inman’s. Well, the internet version of pinching, anyway.

Now, I’ll say right off the blocks, that I like and respect both these guys. I’ve been a fan for years. If the internet is about anything at all, it’s about the kinds of things they do: Inman amuses, makes admirable social commentary and raises money for good causes. Wheaton entertains, makes admirable social commentary and, well, entertains. And yes, he also uses his geek celebrity to aid worthwhile causes too.

In a general philosophical sense, I also agree with what they’re saying here; it’s reasonable to expect that if a money-making venture such as the Huffington Post wants to use your artistic content to help their advertising revenue, then it’s worth more than just their fond appreciation for your efforts.

In my opinion, there is, however, something of a problem with the high moral ground that both Wheaton and Inman are occupying here. They are being just a teensy bit disingenuous. It comes about because of the stature that each of them has gained from the currency that they are dismissing with such disdain. That currency is exposure.

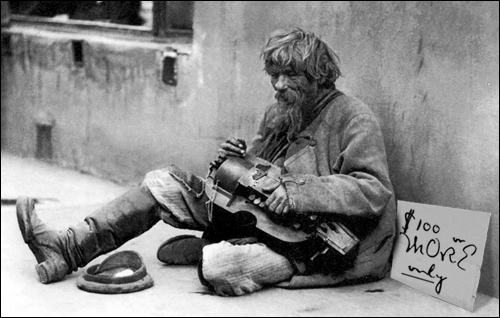

From where I stand, the equation looks very different to what I expect it does to Will Wheaton or Matt Inman. If I was given the same deal as Wheaton, and the HuffPo asked if they could carry this very article, what am I going to do? If they offer me the ‘exposure’ deal, my options are to take it and get exposure or don’t take it and reach my usual two dozen readers. No-one doubts that the best outcome would be to get paid and get the exposure, but likewise, it should be obvious to pretty much anyone that the worst deal is to end up with no money and no exposure. It’s all very well for Wheaton and Inman to tell other people that they should accept nothing less than proper recompense for their efforts, but they are not other people.

As I said some years ago in my post The King is Dead! Long Live the King!, we are now in an age where creative content is worth – in monetary terms – exactly (and only) what people are prepared to pay for it. You can put whatever pecuniary value you like upon it, but that’s completely arbitrary in the eyes of anyone else.

The problem is not an easy one to parse. I’m a creator, and my stuff is indisputably worth a few coins. Isn’t it? But what? Is it worth as much as Will Wheaton’s stuff or Matt Inman’s stuff? No? Then why not? You see what’s going on here, don’t you? There’s a level of artistic value – and corresponding monetary value – assigned to the work of those guys, but how do you calculate the worth of that? I’m going to put it out there that it’s not just value based on the work itself, but rather a combination of things including how much exposure they get. Sure, they do good stuff, but without the exposure, the good stuff is only worth something to the two dozen loyal followers of their blog/band/comic/games-club newsletter. LOTS of people do good stuff.

And that’s the crux of it: with so much stuff being done – and so much good stuff being done – with so many artists and musicians and writers doing their thing, it’s very very hard to rise above the noise. Money is nice to have, but in the great big ocean that is the internet, without exposure, you’ve got nothing. Proper compensation depends a lot on where exactly you are in the food chain. Matt and Will can afford to say no to the HuffPo because it really doesn’t matter to them – they need neither money, nor exposure.

Now, I don’t want to sound like I’m defending the Huffington Post here – I’m really not. I think that they’re unprincipled opportunists (there goes my chance of HuffPo glory) and that they’re wrong to exploit the talents and hard work of others in order to line their own coffers. As long as people are willing to provide them free content, though, this exploitation is never going to go away. I think you can work out, without me putting it down in detail, that there are a lot of reasons that people will continue to provide their content – good content – for free. As I have said in the past, if you are an artist or a writer or a musician, the people doing that are your competition. It’s just entirely irrelevant insisting that your art is worth something if no-one wants to actually pay for it. Whether you like it or not, that’s the world in which we now exist, and it’s simply pointless raising a fist and shaking it at that fact.

It comes down to basic commonsense and survival strategies. Sure, your efforts have value, but the value might not necessarily be financial. If that value can be parlayed into money, great. If it can’t, then decide whether there is other opportunity to be had. If that opportunity is exposure, and you could use some exposure, then take it. If that opportunity is connection, and you need connections, then take it. If there is no advantage in making a deal, then don’t make the deal. The only bad exchange is one where you feel an inequality exists. But don’t let someone else tell you what that inequality is.

Matt Inman and Will Wheaton undoubtedly have your best interests at heart. They’ve just forgotten that as you’re attempting to get your head above the crowd, you sometimes don’t have the luxury of insisting on your principles.