May Contain Traces of Nuts*

This is a little bag of snacky-type things they hand out on Vietnam Airlines.

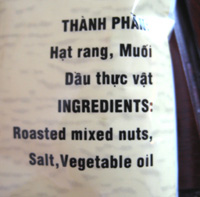

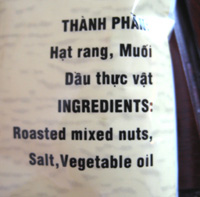

This is the ingredient list on the back:

So far so good. Roasted mixed nuts, salt, vegetable oil. Yep, you know exactly what you’re gonna see when you open that little packet, right?

Wrong! You are in Vietnam, remember, where all rules and laws are merely suggestions.

This is what you’re really going to see:

I have marked for you the actual nuts. Yes, you counted right, three (3) cashews. Which as my friend Simon pointed out, are not even technically nuts. Everything else is definitely not a nut, even the cunning little things that look like peanuts. There are peas, little starchy corn things, and the fake peanuts that are probably made of some kind of crunchy soy product.

True, there was salt (probably – it tasted salty), and vegetable oil (I guess being charitable it could even have been peanut oil…). All in all though, the ingredient list is a much better guide to what’s not in the packet.

I had such a great time in Vietnam.

In Quang Ngai City, where I spent most of my time, there is a new supermarket. We love the supermarket. It is a place where you can spend a good few hours browsing.

In the liquor section, there was a bottle of wine which was labelled ‘Wine with Young Bees’. Floating in the bottom inch and a half of the bottle was a sludge of bee larvae. I held it up and to an old man who was watching us curiously examining the swirling insect brood.

“Good?” I mimed, with a big smile and a raise of the eyebrows.

“Nope”, he mimed back, shaking his head and making a face that said “this is one of the most disgusting things ever invented. I don’t know what they were thinking.”

Outside the supermarket, the road is divided into two sets of two lanes by a median strip. This is the only median strip in Quang Ngai. A median strip in Quang Ngai makes about a much sense as an amber traffic light.

You don’t need to understand Vietnamese to get the sense of perplexity people feel about the median strip.

“Why have they done this? What – we are supposed to cycle all the way down the end of this to the corner, turn around and come back to get to something on the other side? Why are they messing with our heads like this? Next they’ll be coming up with some daft concept like, oh, saying you can only go one way down a street or something.”

Consequently, if you need to get to a place on the other side of the median strip from where you are, you just ignore it! You just get on the other side of the median strip and cycle to where you want to be. Like it doesn’t exist.

I love Vietnam. Did I mention?

___________________________________________________________________________

*If you’re lucky.