Sat 24 Jan 2015

The Girl With Kaleidoscope Eyes

Posted by anaglyph under Hokum, Movies, Rant

[8] Comments

The last couple of years has seen the release of not one, but three science fiction movies starring Scarlett Johannson: Spike Jonze’s wonderful Her, Jonathon Glazer’s remarkable Under the Skin and more recently, Luc Besson’s Lucy. It’s hard not to speculate on why Ms Johannson was cast in these three films; in the first she plays a disembodied computer intelligence bent on achieving – and then escaping – humanness, in the second, an alien bent on absorbing (literally), and then attempting to embrace, humanness, and in Besson’s film, a human who through unfortunate circumstances has the transcendence of her humanness thrust upon her. I can only assume Ms Johansson’s resumé has a description in it that reads something like “Possesses an other-worldly beauty”, and that directors haven’t quite understood that to be a metaphor.

It is the last of those three efforts that we’re going to examine today on TCA, and you can probably tell by the lack of any superlative attached to the mention of Mr Besson’s film, above, that I’m having trouble finding nice things to say about Lucy. In fact, I was just going to add that this review will contain spoilers when I thought that there is nothing I could do in my wildest efforts to spoil this disaster of a movie any more than it thoroughly spoils itself.

Out of the starting gate, there’s a conceit that was hinted at in the trailers for the film and which I really despise: the ridiculous and completely debunked myth that humans only use 10% of their brains. What I hadn’t realised is that this dumb piece of claptrap is actually the focal plot device of the whole piece, and is relentlessly bashed across the heads of the audience from the first frame to the last. Whatever the case, I entered the story fully prepared to file it away as a deus ex machina of the tale, and accepting it under the Willing Suspension of Disbelief clause. In the end, I couldn’t do it due to the ‘bashing-across-the-head’ problem previously mentioned, but it turns out that it didn’t matter because it’s the least of the film’s stupidities.

The film starts interestingly – but even here my Spidey senses started tingling, I have to admit – with some fancy CGI cell division effects, culminating in a ‘dawn-of-time’ sequence featuring a small ape-like creature that anyone with any scientific literacy will instantly recognise as the progenitor of humans: Australopithecus afarensis, represented here, through inference, by an individual whom scientists have dubbed ‘Lucy’. Clever, huh? Well, yes, it certainly could have been.

Over a sequence of Australopithecus Lucy drinking from a stream, we hear Ms Johannson intoning the words:

“Life was given to us a billion years ago. What have we done with it?”

Remember that phrase because we’ll have cause to review it later.

Transition to modern day Taipei, where our modern day heroine Lucy (Johannson), is viciously tricked by her creep of a boyfriend into delivering a briefcase with some unknown contents to a certain ‘Mr Jang’. It turns out that Mr Jang has a super new designer drug (a sparkly iridescent crystalline blue substance known as CPH4, which looks a lot like bath salts ((CPH4 is twice referred to as a ‘powder’ throughout the movie, which it plainly isn’t. This might seem like a nitpick, but the film is full of these tiny little irritations and after a while they accumulate to have a massive eye-roll quotient))) which he plans to ship to various locations across the world ‘in the intestines’ of a bunch of unwilling mules (including, now, a completely freaked-out Lucy). ((Never mind that this makes no surgical sense whatsoever – if you’re going to open someone up to stick in a drug packet, you just wouldn’t put it inside their intestines.)) It’s a terrifying and disorienting launch into the story, and around here I thought momentarily that, despite my misgivings, I might actually enjoy this movie. The optimism didn’t last long – only to the next scene, as it happens.

Cut to: Morgan Freeman (who is the go-to ‘knowledgeable kindly scientist’ in the same way as Ms Johansson is the go-to trans-human), in the role of Professor Samuel Norman, a neuroscience expert. I use the word ‘expert’ sarcastically, as I doubt that there is a real neuroscientist alive that actually believes the 10% myth. But believe it he does, and he even expands on it using the tried-and-true pseudoscientific tactic of just making shit up. “Most species of animal,” he tells us (without so much as a hint of a wry wink), “use only 3 to 5% of their neural capacity.” I almost snorted my whisky down my shirt, but luckily managed to swallow it. Which is just as well, because after he continues on to wheel out the dumber-than-dumb ‘humans use up to 10%’ factoid, he adds: “But now let’s go on to a special case. The only living creature to use its brain better than us…”

You what? I’m totally on the edge of my seat around here because I HAVE NO IDEA WHAT HE’S GOING TO SAY NEXT!!!

Can you guess it, Cowpokes? Do you know which creature apparently uses a whopping 20% of its neural capacity??? Well, says Prof Norman, it’s dolphins. Yup, not only is this film propagating the idiotic 10% hogwash, it’s starting a whole franchise of its own baloney. I have no idea where this ridiculous notion even came from, as I’ve never heard it before, but accepting for a brief moment that there is any consistency at all to this movie’s internal world, all I can say to you is that the dolphins plainly weren’t in charge of the script.

Meanwhile, Lucy wakes up in a hotel room with a fresh wound across her abdomen, via which, she discovers, a kilo of the previously-mentioned CPH4 has been inserted into her gut, in preparation for her unwilling smuggling trip. Before anything further can happen, however, she is kicked in the stomach by one of her captors, the bag containing the drug ruptures, leaks into her bloodstream and somehow begins the process of overclocking her neural processing abilities.

But before we go on, let’s discuss CPH4.

This amazing substance, we are told, is manufactured by pregnant women in the sixth week of pregnancy. “It’s like an atomic bomb going off for the foetus, and gives it all the energy it needs to create every bone in its body”. ((This is total bollocks, needless to say, and doesn’t in any way suggest why it would have utility as a recreational drug. I don’t even understand why you would even write it like that. If you’re just inventing a substance, why not make it some kind of neuro-active agent that you could at least pass off as a new cool hallucinogen or something. This is just one of many witless gaffs made by the film.)) The stuff inside Lucy is a synthetic analog of the natural version and of which she has metabolised a full 500 grams before she gets a surgeon (at gunpoint) to remove the other half from her stomach. Since there are three other implanted mules, this informs us that there are only 3.5 kilos of the stuff in existence in the whole world, apparently. Remember this fact, because it will become germane.

A this point, Lucy’s brain has achieved, we are informed by one of the relentless and completely arbitrary title cards tasked with keeping us up to date on exactly how smart she is, 20% of its operational function. That’s dolphin level, pal. This allows her to suddenly be a martial arts expert, understand any language she likes, change her hair colour at will, control the minds of others and become an expert sharpshooter, all accomplishments for which dolphins have long been admired.

She now simultaneously sets about tracking down the remaining CPH4 (which has travelled to distant cities in the guts of the other mules) and getting in contact with Professor Norman in order to impart some kind of information to him (what it is, exactly, and to what end she wants to pass it on is never really made clear). Here, we’re at about the halfway point of the movie, and from here to the end the film is just a guffaw-laden hack-fest, with few redeeming features.

In one of many completely daft sequences, while she is travelling on a plane to meet Professor Norman, Lucy’s body begins to disintegrate, and she manages to stop it from doing so by scoffing down mouthfuls of the remaining CPH4 she has in her possession. I was completely at a loss to understand why this was happening. Maybe she shouldn’t have had that champagne that she ordered from the cabin attendant? ((And why the hell was she travelling Business Class? SURELY with her new mind control skills she could have nabbed herself a First Class cabin?))

As Lucy’s brain power accelerates upward of 50%, we learn that she now has control over radio frequencies and computers, over matter and even over gravity.

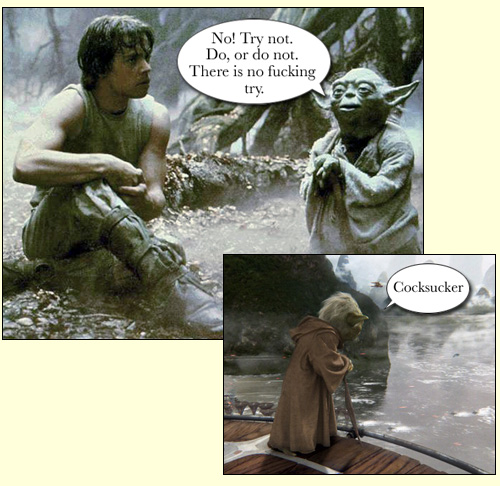

With all that under her belt, she undertakes a ruthless mission to retrieve the other 3 kilos of CPH4. This invokes the obligatory car chase, some more gunplay and a serving of fancy telekinesis. At one point, she quite theatrically sticks some thugs and their weapons to the roof of a corridor. Why she doesn’t simply render them all instantly unconscious as she did to a room full of cops a few scenes earlier is fairly hard to fathom. Whatever the case, the relentless pursuit of the CPH4 all seems so perplexing and unnecessary; if Lucy can control matter, how is it that she can’t just conjure up more of the drug at whim, or, even more conveniently, just re-configure her biology to suit? ((Follow me here: if pregnant women are able to manufacture CPH4, then, given her superhuman powers, surely it’s a doddle for her to rejig her own body to make gallons of the stuff? I really hate it when this kind of thing happens in a science fiction movie. An audience will accept all kind of bizarre wackiness in the name of speculation or fantasy, but Rule #1 in fantastic fiction writing is that YOU MUST BE TRUE TO YOUR OWN INTERNAL LOGIC. If you break this rule, the audience has nothing to hang on to, and will become adrift in the silliness you’re peddling.))

Lucy eventually arrives at Professor Norman’s laboratory and sets about turning herself into a computer. Or something. I’d completely lost interest at this stage, because the movie tipped into the kind of hippy-trippy vacuous science-fiction buffoonery that you usually find in the most B-grade of the genre. Various berserk things happen. This is what I remember:

•Lucy gets injected with the remaining 3 kilos of CPH4 and sets about vanishing all the walls of the building, whereupon everyone finds themselves in a White Void. I really HATE the White Void. The White Void seems to be director language for “we’ve gone off the edge of the known universe, so there’s nothing left to express it except acres of whiteness”. You will remember the White Void from many places, including Doctor Who, The Matrix and Pirates of the Carribean: At World’s End. It’s a lazy, inelegant and unsatisfying trope, and anyone who uses it instantly loses a star from my rating.

•She flashes back through time to pre-history, enabling an absolutely gag-making moment between ‘God’ Lucy and Australopithecus Lucy. Think Michelangelo. Yes, it was that. ((Seriously, that’s the kind of thing that enters a scriptwriter’s brain for a split second before the Big Red Mind Pen strikes it out of existence for ever.))

•She exudes black crawly stuff that wrecks all the gear in the lab.

•Then, she disappears leaving only her little black dress and shoes. All I can think of at this point is that it’s a perfect allegory for the film disappearing up its own asshole.

Meanwhile, as all this is happening, Mr Jang (remember him from earlier?) is outside shooting up everyone in sight in an effort to get back his bags of CPH4. His sudden appearance in the destroyed lab was so incongruous and meaningless it actually made me laugh. It doesn’t freak him out even in the slightest that he’s blasted through a door with a rocket launcher to find himself in a white infinity of nothingness. If ever there was a pinnacle of cinema-character single-mindedness, this guy is IT. He just wants his drugs back.

Finally, in one of the silliest moments I think I’ve ever seen in a science fiction movie, Computerlucy (for she has apparently become some kind of omnipresent entity living inside the mobile phone network) exudes a crawly black tentacle and hands to Professor Norman her vast resource of newly gained insight.

On a sparkly USB drive. Stop laughing, I’m serious.

Over a craning aerial shot of the destroyed lab, the perplexed scientists holding the sparkly USB drive, and the bloody bullet-riddled corpse of the recently-deceased Mr Jang (yep, crime doesn’t pay), we once again hear that early disembodied voiceover from Ms Johannson, now laden with meaning and import:

“Life was given to us a billion years ago. But now you know what to do with it.”

The End.

NOOOO! NO! We DO NOT KNOW what to do with it! Give me a hint! Is it to put life on a USB drive? Is it to not pursue our drug habits? Is it to find a way to make White Voids? Blue crystals? Dolphin computers? THANKS TO THIS MOVIE, I HAVEN’T GOT THE FAINTEST IDEA WHAT I’M SUPPOSED TO BE DOING WITH MY LIFE. Which is no different to before I saw the movie, only now I think maybe I’m missing something.

Unless, of course, what she’s saying has a meta-meaning: “Why did you waste two hours watching this rubbish when you could have been – oh, I dunno – kicking rocks down on the railway crossing?” In which case I really did get that.

Like so many half-baked sci-fi efforts before it (such as The Black Hole; Sunshine; Sphere to stand just a few in the dunce corner), Lucy is crushed under the weight of its own pretensions. It attempts to be simultaneously an action thriller and a psycho-philosophical musing on human destiny, but achieves neither of those aims, first, because there just isn’t enough cool action and second because it has the philosophical insight of a high-school stoner. When I saw the trailer I was really hoping for something like La Femme Nikita meets Limitless, only better. Instead we got Streetfighter meets What the Bleep Do We Know?, only worse.

As far as Lucy is concerned, on the Scale of Movie Intelligence, the needle is barely nudging 2%. If there is any kind of lesson to be learnt here at all, it is that we should probably be leaving the good science fiction movie-making to dolphins.

Also, this.