Crowdfunding is a really great idea. It is simultaneously a really crappy idea. Needless to say, like most things, it’s human greed and the relentless pursuit of money that determines which of those two things it is for any given case.

I like the idea behind crowdfunding, and have invested in a number of terrific projects. I’ve even run a crowdfunder of my own, with moderate success. When I choose crowdfunders in which to participate, I’m as careful as I can be to vet them for plausibility and likelihood of success – there is obviously no point in sticking your money in something that is based on pseudoscience, for example, as so many are. Nor is it worth participating in something that is just unachievable due to someone’s inability to grasp basic laws of physics. So I choose my allegiances cautiously.

It is, therefore, hugely disappointing for me to have invested in a crowdfunder that tanks, as did the ARKYD Space Telescope Kickstarter yesterday.

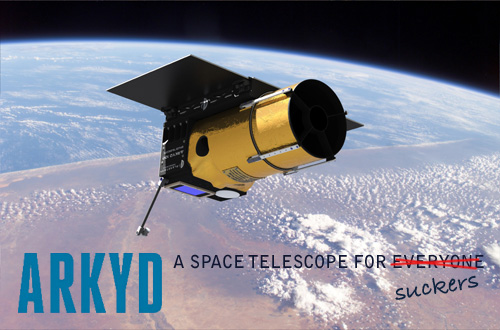

A few years back, a company called Planetary Resources launched the Kickstarter for a publicly funded space telescope – “a space telescope for everyone” – with the promise of a ‘selfie in space’ as one of the primary perks. This entailed contributors being able to upload an image of their choice to a screen on the ARKYD telescope, and then having it rephotographed in orbit high above the earth. As perks go, that’s a pretty damn catchy one. The eventual goal of the project was to facilitate public accessibility to time on an actual space-telescope. There was to be a particular emphasis on affordable access for educational institutions and other bodies and persons who would otherwise never be able to afford such opportunities. Wow, what a cool thing, right?

The ARKYD Project Kickstarter was asking for $1 million (a substantial figure by crowdfunder standards) to achieve its aims, and it made the milepost easily, quickly surpassing it by another half million. The Kickstarter project assessment made it quite clear that such an undertaking was not without risks, and indeed, the ARKYD encountered a few of them, including the explosion of an early launch vehicle. Not many Kickstarters can claim that kind of setback, but it is, after all, rocket science. All that taken under consideration, the ARKYD Kickstarter presented as a very well thought-out achievable project, with a highly-credentialled engineering and development team, a lengthy but plausible production schedule and most encouragingly of all, a great deal of support from science experts, space science advocates and fans across the planet. When I invested in ARKYD, I was completely confident that these people could deliver.

So I was pretty taken aback when – without any warning at all – Planetary Resources announced that they were shutting down their Kickstarter. I was especially dissatisfied with the reasons given by Chris Lewicki, PR’s President and Chief Engineer, for the abandonment of the project:

When we closed the campaign in June of 2013, we were confident that the tremendous enthusiasm from around the world would translate into continued financial support outside of the Kickstarter community to move our idea forward… but, what we discovered was unfortunate. Aside from all the progress we made in the underlying technology, the follow-on interest from the business and educational sectors to expand the ARKYD campaign into a fully-supported mission did not exist as we had anticipated. We have explored and exhausted a variety of opportunities big and small for the financial backing necessary to complete the project.

You see, nowhere in the original Kickstarter pitch is it mentioned that the project is contingent upon this ‘follow-on interest from the business and educational sectors’. In fact, re-reading it, as I just did, gives exactly the opposite impression: that the money raised is more than enough to do the job, even prompting a host of ‘stretch goals’ to further enhance the scope of possibility. Like most people, I have no clue how much it costs to put a small satellite in space, and while I did vaguely wonder if a million bucks was a tad ambitious, what would I know, really? I mean, I’d given my money to experts. Like the other seventeen & a half thousand backers, I was hugely excited by the proposed outcome of space science for ‘all the wonder junkies out there’ as PR so colourfully put it in their promotional video. Lewicki’s announcement makes it sound like the only thing the money was used for was the development of the technology. I want you to keep that thought in mind as we continue.

Those of you who’ve been following this saga might at this point be interjecting that Planetary Resources is offering a refund to all backers on application, so what’s the beef? Yes, it’s true – all investors in ARKYD have been invited to claim full refund of their money, as of this morning. That seems fair enough – generous, even, considering that there are truckloads of crowdfunders that go under without so much as a thankyou note.

There is, however, a backstory that casts quite a different light on this ‘generosity’. Planetary Resources’ ARKYD ‘space telescope for everyone’ has been iced, but the company itself has just raised over $21 million for their Ceres project, an array of earth-observation satellites – ARKYD-like space telescopes – that are designed to monitor natural resources for anyone who wants to pay for the information.

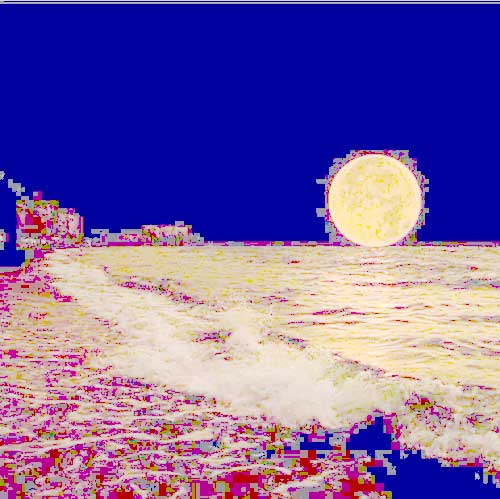

That little satellite telescope in the picture there? That’s the ARKYD that we all expected to see doing publicly-funded space science.

You see what just happened, right? The $1.5 million that optimistic, excited kids (and adults) funnelled into Planetary Resources ARKYD Space Telescope, was essentially an interest-free loan to a mining company to help them develop their technology.

Now Planetary Resources has never hidden their mining ambitions. They make a big deal on their website about their future as an ‘asteroid mining’ company. But this is something quite different. If it had been presented to most people that they would be contributing their dollars interest free to a company whose aim was to make money out of exploiting the natural resources of the earth, I’m pretty damn sure the ARKYD Kickstarter wouldn’t have raised a cent.

I’m fuming angry at Planetary Resources. Their $21.1 million dollar windfall will allow them to pay back their ‘loan’ from the ARKYD project and still leave them a cool 20 mill to set up a system that will let them put their greedy hands deep into the grubby pockets of mining companies all over the world. Worst of all, they just couldn’t be bothered delivering on their promise to give enthusiastic young people the opportunity to be part of humanity’s great space adventure. It appears that they thought the whole ‘space telescope for everyone’ business was just one big headache that got in the way of earning money. ((I quite understand that it now looks probable that to continue with ARKYD would have cost them something more than just abandoning the project outright and refunding everyone’s money – but that’s the whole pivot of my objection to what has happened. If this wasn’t going to be achievable from the outset with the money requested from the Kickstarter, then they’ve just fucked up, which is not a great endorsement of a their business acumen – investors take note. Not only that, they lied to their contributors after the project was scuttled, by telling them that the whole viability of ARKYD was entirely speculative and contingent upon attracting what we must now assume to be substantial investment from other sources. I, for one, would have been much more cautious about forking out if I’d known that. On the other hand, if Planetary Resources does know what they’re doing, then they simply exploited the good nature of kids and adults who thought they were getting to be part of a great space adventure. EITHER WAY, these people look bad)).